There are two types of disciplined people: those who take consistent action through sheer willpower and those who do it without the use of willpower.

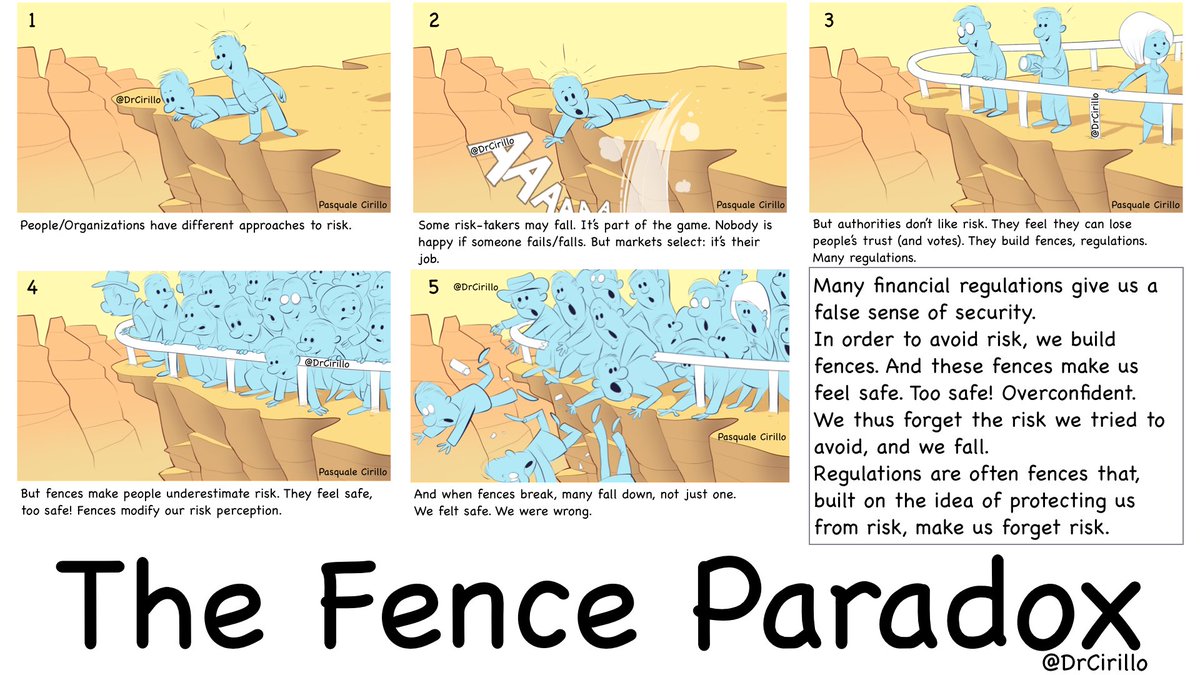

Italian scholar Pasquale Cirillo clearly explains the Fence Paradox with the following illustration.

I already talked about the Fence Paradox in a previous post. In this essay, I will talk about its implications in medicine.

The Fence Paradox and risk homeostasis

Every time a new technology allows us to behave in the old way but more safely, or to behave in a new way which is more beneficial to us short-term and which has the same perceived risk as the old one, humans always choose the latter. This phenomenon is called risk homeostasis, and is the basis for the Fence Paradox. (More technically: humans always choose to transfer the benefit of a new technology from perceived safety to efficiency, if allowed to do so). In particular, risk homeostasis holds that we use our estimate of risk to evaluate how much we can push our luck in performing an action more efficiently. Since we use higher-frequency, lower-damage incidents to estimate the risk, and we adjust our behavior in a riskier way to keep the frequency of higher-frequency, lower-damage incidents constant in order to reap efficiency benefits, any technology which reduces our exposure to higher-frequency, lower-damage incidents only will cause us to increase our exposure to lower-frequency, high-damage incidents.

Iatrogenics: one step forward, two steps back

In his book Antifragile, Nassim Taleb observes that adult life expectancy only increased of a few years during the second half of the twentieth century [1], in spite of the multiple advances in medicine and in public health availability. How is it possible that these medical advances didn’t improve our lifespan by decades, but merely years? Taleb explains this result with iatrogenics: damage made by the healers.

We can categorize iatrogenics in 3 groups, depending on the process causing them:

- Iatrogenics from side effects: a surgical operation which causes an infection; a medicine which solves a disease but introduces another.

- Iatrogenics from forecasting: forecasting with too much precision leads to fragility. We build walls just thick enough for the earthquake whose magnitude we think we can predict with accuracy; we plan just enough money in the bank to survive for next month and use up all the rest, leaving us vulnerable to any hiccup or unable to benefit from any opportunity which would require cash available.

- Iatrogenics from removing pain or other non fatal symptoms: reducing symptoms leads to increased perceived safety, which, due to risk homeostasis, leads to increased risk-taking and, ultimately, to fatal incidents.

In Antifragile, Taleb discusses extensively the first two; here, I will talk about the third.

Made To Act

Our nervous system is not a machine to perceive reality correctly; but a machine to take decisions correctly. Optical illusions (such as our tendency to see faces where there aren’t) do not make sense if our brain’s role is to perceive reality as it is; but they do make a lot of sense if we consider our brain role to be to take the right decisions (for example, fleeing when we perceive a tiger in the bushes, even if its face is not fully visible).

Similarly, pain is not much a signal of damage (the reality) but a signal designed to make us take the right decisions (for example, stop doing what hurt us). Removing pain means increasing the risk of future damage.

(My book “The Control Heuristic, 2nd edition” talks about these topics in greater detail.)

Pain as a learning signal

Removing pain is just like building a fence. Sure, we avoid what feels bad in the moment. However, we also build a support which allows us to lean on it and to adopt even riskier behaviors. Pain is there for a reason: to change our behavior. If we remove the symptomatic pain, we remove a learning opportunity and end up doing more of what is damaging us. We end up leaning on the fence, till we break it. (I am not advocating against removing all forms of pain. Pain in terminal patients should be alleviated, as should the intense pain coming from injuries where there has already been enough pain to constitute a learning moment. I am against removing the lighter forms of pain which are learning signals for us.)

Chronic pain

Coelho wrote: “When you keep encountering the same obstacle over and over again, it’s life’s way to teach you a lesson you don’t want to learn.” So is chronic pain, when derived from bad posture, bad life habits or stress. Chronic pain is there to teach us a lesson: stop doing what you were doing; change your life towards an healthier alternative. And yet, we prefer try to close our eyes and swallow a pill to make the pain go away, in order to be able to persevere in the unhealthy habit. We prefer leaning on the fence, till we break it. Instead, we should accept pain not as a signal to silence, but as a signal to listen to [2] [3].

Surgical procedures

Ugur Kukuc suggested that the use of contact-force sensors on catheters is an example of the Fence Paradox in surgical medicine. Normal catheters used for atrial fibrillation ablation only cause atrioesophageal fistulae (a fatal side effect) on 0.9% of interventions; catheters with contact-force sensors, designed to help doctors proceed more safely, end up causing fistulae on 5.4% of interventions, a 4-folds increase. Could it be because of the increased perception of safety? Further studies have been recommended.

The magical pill

Imagine the following scenario: scientists discover a magical pill which, if taken once per day, removes the negative effects of smoking five cigarettes per day (people can only safely take one pill per day; the pill has no side effects if taken in such a dose). The discovery is celebrated, and the scientists involved win a Nobel prize. However, what is a likely result, in the long term? Those who smoked 1-2 cigarettes per day keep smoking them, and are spared from health problems. Anyway, they were the ones less likely to have severe problems, so this is a very small win. Of those who smoked five cigarettes, very few will keep smoking only five: most of them will end up smoking five more cigarettes than they did before. More importantly, a novel message will spread: “It is now safe to smoke up to five cigarettes per day!”. Millions of people start smoking. How many of them will stop at five cigarettes per day? Not many, probably. Also, passive smoke will become a much bigger issue. Finally: the extensive tests before release established that the pill has no side effect if taken once per day. But how many people will smoke ten cigarettes and take two pills per day?

In the long term, did the magical pill save or kill people?

Conclusion

Of course, we should heavily invest in medical research and in the productions of technologies (drugs, procedures, instruments, etc.) to keep us healthier. However, we should be careful not to build fences to which people can lie on. We should refrain from technologies that suppress pain when it is a learning signal. We should understand that if a new technology allows us to either do something more safely or more efficiently, humans will never choose the former, and that this will cause a shift from many small damages to a few catastrophes (will the efficiency gain ultimately worth it?). We should design and evaluate technologies not only taking into account their short-term gain, but, more importantly, the long-term shift in behavior they will cause.

*****

Notes:

[1]: From 51.2 to 58.2 years old in the 1952-2002 period, for adults of age 20; source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

[2]: I have some skin in the game in saying this. I have been suffering for 2 years of chronic pain. It took me some time and courage to understand that the way to go was not to take pills, but rather not to take them, and try to improve my lifestyle and posture. It took me months of pain to get me to do something to improve the way I was sitting and working. I am now almost free of pain, and living an healthier life.

[3]: On this topic, I suggest reading John Sarno’s The Divided Mind.