Growth obtained through short-term tactics eventually plateaus. It’s a dead end.

The US response to the pandemic has been hindered by the FDA having waited until late February to approve non-government test kits and early March to relax test eligibility guidelines (the latter having been a consequence of the former). The problem is not regulation, which has its benefits, such as protecting the population from diagnostics and drugs which might not be safe. The problem is that regulations have been optimized for the times of quiet growth alone, without a thought to eventual emergencies such as the current pandemic.

Countries that have been successful in their early response to the COVID-19 pandemic had been quick to interrupt their normal procedures at the early signs of warning, just like circuit-breakers automatically activate to protect electric systems from damage.

For example, Singapore has been quick to offer free testing and free hospitalization to its residents suspected of having contracted the COVID-19 virus, even though it is a private-healthcare system just like the US. It is a false dichotomy that a healthcare system must always be public or always private. It can be private, with a circuit-breaker to make it public in times of need.

Similarly, the FDA could have adopted a circuit-breaker in the form of automatic approval of test kits from reliable developers (for example, defined as those which got approval for at least 5 kits for unrelated conditions over the previous 5 years) kicking in whenever there is a need for such kits and the CDC is unable to supply them within, say, two weeks.

Singapore is small enough for change to propagate fast, so it didn’t need a formal circuit breaker: its agile government swiftly introduced an ad-hoc law. The US is a much larger country and thus badly needs circuit breakers, such as a law that automatically kicks in during outbreaks and makes testing free or caps its price, so that the infected can be isolated quickly, protecting everyone – them, and the healthy.

Just like the fact that everyone uses the elevator to climb skyscrapers has never been an excuse not to build an emergency staircase to be used in case of a fire, optimizing a regulation for the times of quiet growth should not be a reason to not have emergency procedures already in place ready to be triggered in case of a crisis.

One peculiarity of circuit breakers is that they represent laws that countries tend to pass anyway during emergencies, but due to bureaucratic slowdowns, often only do so when it is already too late. This is undesirable, for every day that passes, it becomes more expensive to achieve the same result. For example, finding and isolating all the infected might have been a relatively small cost at the beginning of an outbreak, but doing so at a later stage is extremely expensive, as the number of people to track down and test becomes increasingly higher.

Circuit breakers in Nature

Circuit breakers are embedded in our nervous system. When you touch something really hot, your hand retracts thanks to a reflex. This is done without involving the brain. Even though electrical signals travel fast through our nerves, evolution correctly determined that having them reach the central authority and travel back to the muscles takes too long. Instead, reflexes – our body’s circuit breakers – are evaluated and executed locally, by local neurons.

The characteristics of circuit breakers

Circuit breakers are alternative regulations that kick-in in case of emergency.

Circuit breakers must be automatically triggered. Their whole point is to allow for fast adaptation when an emergency comes, so that the maximum result can be achieved when the costs for doing so are still low. A circuit breaker that requires a decision from a centralized body will be too slow. For example, a central institution such as the FDA could have designed a circuit-breaker that allows laboratories with a good reputation to produce their own test kits during a pandemic, in case the CDC would be unable to supply them within two weeks. This circuit breaker would allow the relevant laboratories to begin design and production immediately, without having to wait for the authorization of central institutions. For the same reason, the definition of “pandemic” should be something that a laboratory can autonomously and objectively identify without having to wait for the WHO to declare one (e.g., “a pandemic is an outbreak with confirmed local community transmission in at least two continents”).

Circuit breakers should be based on leading indicators. Countries such as the US, which adopted a lockdown after evidence of tens of deaths, had a slow reaction that allowed the virus to gain a foothold. Conversely, Taiwan – which began screening passengers from Wuhan as early as the 5th of January – reacted fast because it was observing leading indicators, such as WHO’s international reports on anomalous illnesses.

The number of deaths is a lagging indicator: it describes problems after they happened. Conversely, community transmission in foreign countries is a leading indicator: it describes an outbreak that might happen, thus giving a chance to react before it’s too late. A system that relies on lagging indicators to trigger a reaction is necessarily slower and thus brittler than one which relies on leading indicators. Effective circuit breakers observe leading indicators. Only this way, they will trigger before the problem hits the country hard.

The conditions triggering circuit breakers must be clear and objective enough so that central agencies can trust that local activations will be fair. The conditions cannot be “gameable”, nor there should be much subjectivity in their definition. This is to protect the three parties involved: the central government is reassured that local agencies will execute on the circuit breaker only when warranted, the local agencies are confident that there won’t be any risk of them being held up responsible for the costs of activating the circuit breaker in case of a false positive (“they were following the law”) and the population is reassured that the circuit breakers will be triggered and they will get the protection they need, without the risk of any bureaucratic delay.

On the other side, circuit breakers should still preserve the accountability of the companies involved. It should allow for fast action, not reckless one. It is one thing for the FDA to allow laboratories to test new drugs without having to wait for the approval to do so; it is another thing to allow them to bring products to the market without having tested them in clinical trials.

If the FDA allowed reputable labs to produce any kind of drug or test kit without approval, it would be a question of months before a greedy executive unnecessarily pushes a dangerous product to the market. It makes sense to relax regulations only when the cost of not doing so is high – when the alternatives are tail risks such as the deaths of thousands.

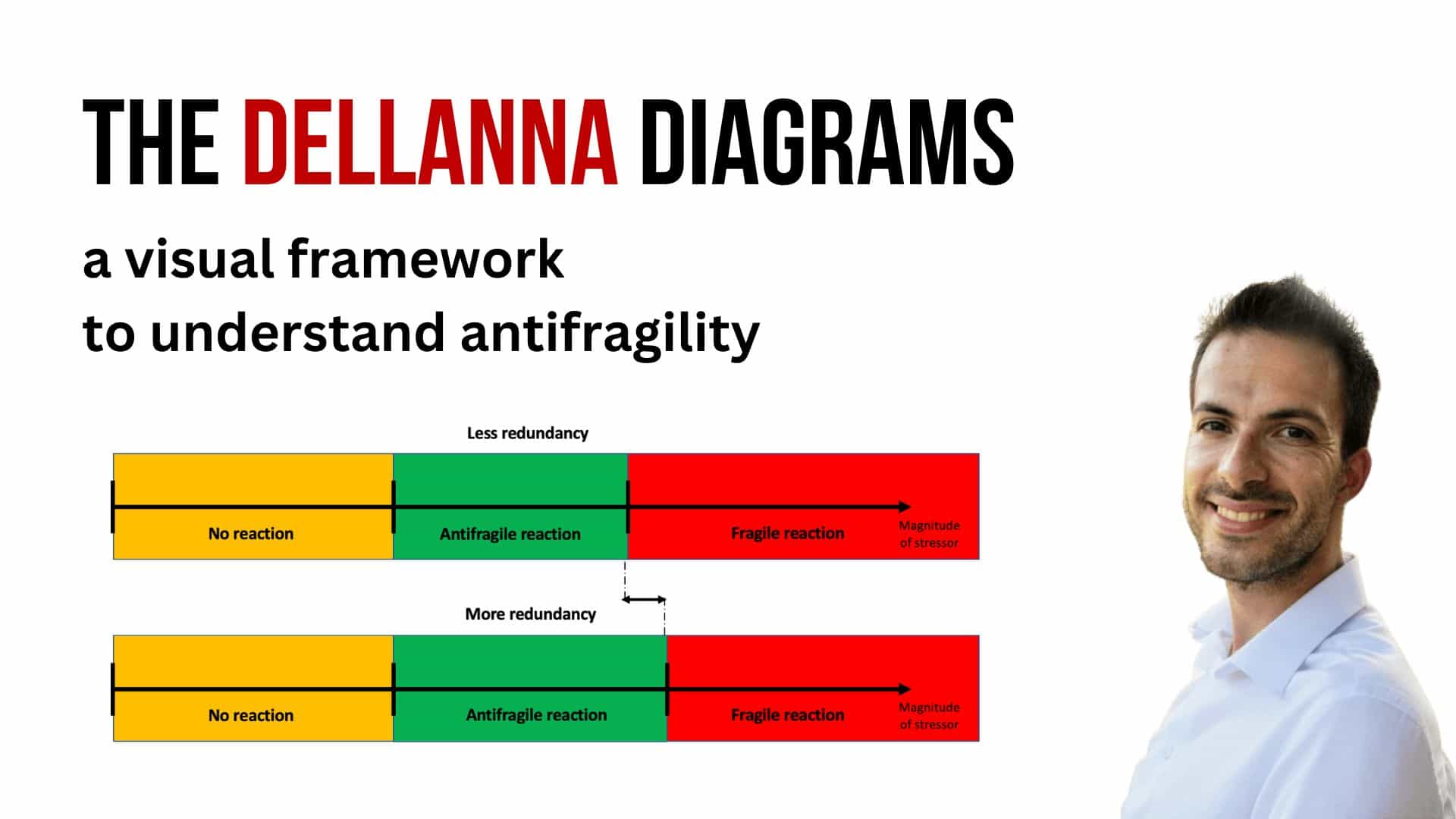

Circuit breakers might be triggered by false positives: the possibility of a crisis that does not materialize. This is not a bug. Because no emergency can be fully predictable, in order to avoid false negatives (failing to trigger before an emergency which does realize), it is necessary to have at least a few false positives. Because it is extremely likely that there will be a few false positives for each false negative, it is necessary that the cost of false positives is way lower than the cost of false negatives, so that the weighted result is a net positive. Therefore, circuit breakers are a useful technology only in case of tail risks – those risks whose consequences are large enough to justify apparent “over-reactions” to false positives.

Moreover, circuit breakers must be designed so that the cost of having triggered them on a false alarm is much smaller than the cost of not having triggered in case of need. Otherwise, those opposing them will have a strong case for their abolition. For example, Singapore decided to go for a private healthcare system keeping the optionality to convert it to public during pandemics, for the treatments related to pandemic. The costs of a false positive – providing free testing to people showing the symptoms and free hospitalization for those testing positive during an outbreak which turns out to be smaller than expected – are tiny compared to a false negative such as letting a deadly pandemic escalate because those who could not afford healthcare had been silent spreaders.

Lessons

The countries that managed to contain the COVID-19 better share one commonality: they acted early.

There are reasons for regulation – namely, to protect the population from harm. However, the strictness of regulation should be defined by weighting the costs of reckless action to the costs of slow action. The latter is amplified during a crisis, and regulations have to temporarily relax to restore the trade-off to optimality.

Singapore rapidly introduced free testing and hospitalization, and Taiwan didn’t wait to screen travelers from Wuhan. Due to their sheer size, it is impossible for the US to relax regulations during an emergency as fast as these smaller countries did. Circuit breakers are a tool that allows a country to act fast during emergencies, even with not-so-competent leaders or with competent leaders having to fight a swamping bureaucracy.

Enshrinement

Ideally, circuit breakers should be enshrined in constitutions or statutes. This is to prevent the risk that, after a few years of peaceful growth, they are seen as vestigial remains of a distant past and are repealed.

The reason this article is published now, in the midst of a crisis, is because only in such times we can feel the dire need for automatic regulations protecting us, and we can remember the problems with having to rely on centralized decision-makers in times where quick action is the difference between a bump in our lives and a catastrophe.

If the circuit breakers do not become law in the short-term when the scars are fresh, they will never see the light; at least not in any formulation that actually guarantees that they will trigger when meant to. And if they are not enshrined into a constitution or into a statute, they will be repealed before their common-sense usefulness saves lives.

Preventing permanent state extension

It often happens, in countries without circuit breakers, that during an emergency, the state extends its powers and takes a larger role than its usual one. There is a risk that, after the end of the emergency, the state crystallizes in its extended form and attempts to permanently keep the temporary powers it granted itself.

Circuit breakers avoid a permanent overextension of the state, by preventing it in the first place (if the circuit breaker triggers quickly, the crisis might be averted) or by regulating the transition – if the state is granted powers during the emergency, it’s the circuit breaker which granted them and thus removes them. It’s all automatic, and this makes the country less fragile.

Another advantage of circuit breakers is that they partially prevent emergency relief bills from being stuffed with unwanted provisions, such as bailouts to mismanaged companies. By laying down in advance some emergency response, they reduce the need from the legislators to pass opaque emergency bills.

Conclusions

Circuit breakers are necessary tools to make sure that countries can react fast enough to emergencies, when the costs for doing so are still relatively low. As countries continue responding to the crisis, political realities make the window in which concrete institutional change can occur a small one.

Fortunately, circuit breakers are both grounded in theoretical underpinnings and successful enactment by those governments which have learned from previous crises. If the US becomes serious about rebuilding its depleted state capacity, they are also one of the most effective and immediate tools which those taking on this work can employ.