Definition

Ergodicity is a property where the time average of a system equals its ensemble average. In non-ergodic systems, what happens to an individual over time differs from what happens to a group at a single point in time. Most real-world decisions involving risk, investing, and irreversible outcomes are non-ergodic.

On This Page

What is Ergodicity Economics?

Ergodicity Economics is a field of study that considers the implications of ergodicity on mainstream economic theory. It challenges fundamental assumptions in economics, finance, and decision theory.

The core insight is simple but profound: most economic models assume ergodicity, but most real-world situations are non-ergodic. This mismatch explains why theoretically optimal strategies often fail in practice.

For example, it shows how you cannot extrapolate averages in the presence of irreversibility, or how long-term investments require different evaluations than short-term ones. You can find a few examples of these phenomena in the excerpt of the first chapter of my book "Ergodicity", which is available for download on my Excerpts page.

Time Averages vs Ensemble Averages

The distinction between time averages and ensemble averages is the heart of ergodicity economics:

- Ensemble average: What happens to many people at a single point in time. “On average, gamblers break even.”

- Time average: What happens to one person over many periods. “This gambler eventually went bankrupt.”

In an ergodic system, these two averages converge. In a non-ergodic system, they diverge - often dramatically.

The Tale of Two Skiers

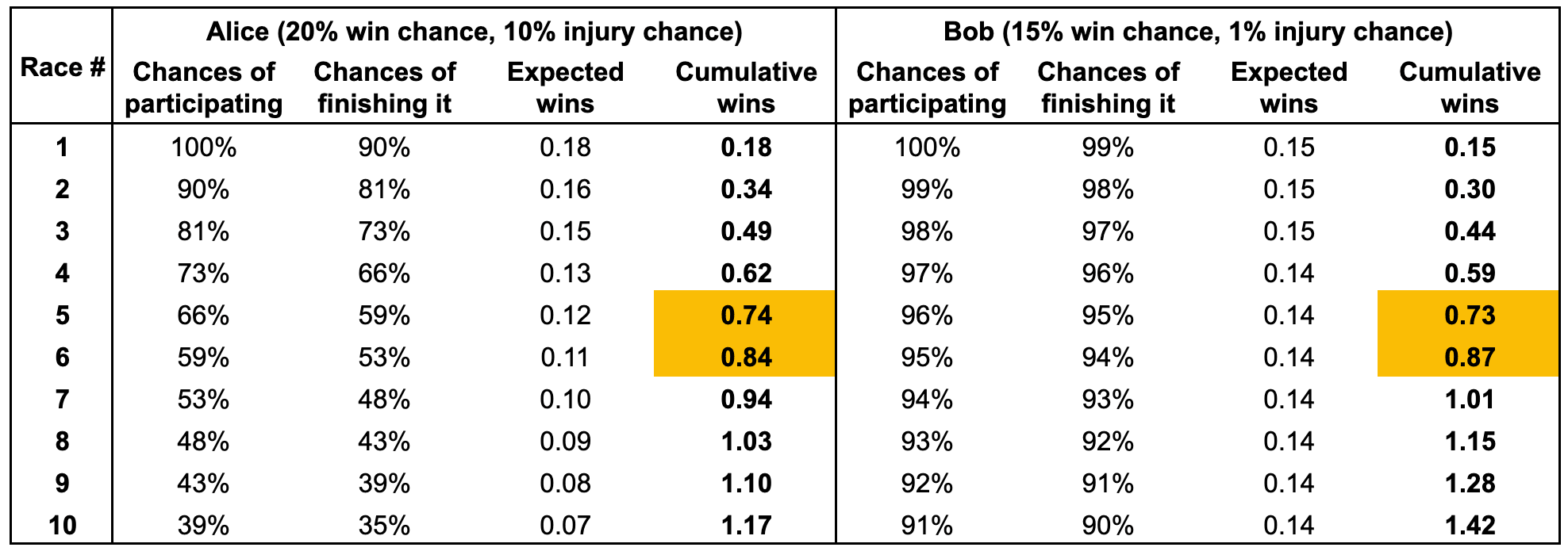

Imagine two cousins, Alice and Bob, who decide to participate in a skiing championship. They have the same skill level, but with one difference: Alice takes more risks, so she has a 20% chance of winning each race and a 10% chance of injuring herself. Bob is more conservative: 15% chance of winning, but only 1% chance of injury.

Which skier wins the most races?

The counterintuitive answer is that it depends on the length of the championship. Alice's strategy is better for championships of up to 5 races, whereas Bob's is better for championships of 6 or more races.

The strategy that produces the best short-term results is not always the strategy that produces the best long-term returns.

Don't Imitate Winners

What if we compared 100 Alices vs. 100 Bobs? The racer with the most wins after 10 races would likely be an Alice, even though on average, Bobs have more wins. The winner's strategy is not always the best strategy. Careful who you decide to imitate.

Want to experience this yourself? Try the Skiing Ergodicity Game or the Russian Roulette Game to feel how small risks compound over time.

For a deeper dive, see my article on Ergodicity in Investing.

Why Ergodicity Matters

Understanding ergodicity transforms how you approach decisions involving risk and uncertainty:

- Expected value can mislead: A bet with positive expected value can still ruin you if outcomes are irreversible.

- Survival trumps optimization: You must stay in the game long enough for averages to matter.

- Time horizon changes everything: The same strategy can be optimal or disastrous depending on how long you play.

Why “Risk Aversion” Is Rational

There is a common belief that people are irrationally risk averse. Consider this game: flip a coin. Heads, you win $1000. Tails, you lose $950. The expected value is +$25 per flip. Yet most people decline. Behavioral economists call this “irrational.”

But real people don't have infinite cash. If you start with $1000 and lose the first flip, you can't play again. Your limitation on the number of times you can play transforms your lifetime outcome.

After two iterations: you have a one-in-four chance of being up $2000, one-in-four of being up $50, and one-in-two chance of being down $950. The behavioral economists who called people “irrationally risk-averse” are the irrational ones.

For a detailed example, see my article on Ergodicity vs Expected Value.

Further readings: Ole Peters's and Alexander Adamou's papers discuss this problem and contain additional examples of how (non-)ergodicity explains the hidden rationality of some risk aversion and of other behaviors that would be irrational in an ideal ergodic world. As far as I know, he was the first to propose ergodicity as the solution to many otherwise puzzling behaviors.

Real-World Applications

Ergodicity has profound implications across many domains:

Investing

Why diversification works, how to size positions, and why most portfolio advice is wrong. The Kelly Criterion offers a mathematically rigorous approach to investing in non-ergodic markets.

Career Decisions

Some career moves are reversible (changing companies) while others are harder to undo (burning bridges, reputation damage). Ergodicity helps identify which risks are worth taking.

Business Strategy

Why startups should focus on survival before growth. Why "move fast and break things" works for some decisions but not others.

Health

Certain health risks are non-ergodic: you cannot "average out" a fatal accident or permanent injury. This explains the asymmetry between prevention and treatment.

Relationships

Trust is non-ergodic: easier to destroy than to build. Understanding this changes how you approach commitments and conflicts.

Try It Yourself: Interactive Games

Experience ergodicity firsthand with these interactive simulations:

- Skiing Game - See how small daily risks compound over a lifetime

- Russian Roulette Game - Watch expected value diverge from actual outcomes

Key Researchers in Ergodicity Economics

Ole Peters is perhaps the researcher who has advanced the most Ergodicity Economics. Namely, he and Alexander Adamou wrote the seminal paper Ergodicity Economics, which inspired my book "Ergodicity" (in fact, the reason I wrote it is that I loved the aforementioned paper but thought it was written in an excessively technical and abstract way, which restricted the audience, and instead I wanted to help laypeople understand this extremely useful idea of ergodicity and its many applications without having to understand the mathematics behind it).

Nassim Nicholas Taleb is the scholar through which I got to know about ergodicity, as he briefly mentions it in his book Skin In The Game.

Other scholars who worked on the topic include Murray Gell-Mann, Ed Thorp, John Larry Kelly Jr., Harry Crane, and Joseph Norman.

Further Reading

My Articles on Ergodicity

- Ergodicity vs Expected Value - Why maximizing expected value can lead to ruin

- Ergodicity in Investing - How to apply ergodicity to portfolio decisions

- Ergodicity and Insurance - Why “bad bets” make sense

- Ergodicity in Career Decisions - Which professional risks are worth taking

- Ergodicity as a Non-Binary Property - Why ergodicity exists on a spectrum

Books on Ergodicity

- Ergodicity by Luca Dellanna - A practical guide focusing on applications rather than theory

- "Skin in The Game" and "Antifragile" by Nassim Nicholas Taleb - Popular introductions to related concepts

Academic Papers

- "Ergodicity Economics" by Ole Peters and Alexander Adamou - The technical reference paper

- "Ergodicity as a Non-Binary Property" - My research on degrees of non-ergodicity

- "The Dynamics of Ergodicity" - Second-order effects in risk-taking

Media Appearances

I have discussed ergodicity on several podcasts including EconTalk with Russ Roberts, Infinite Loops with Jim O'Shaughnessy, and many others. See my full list of podcast appearances.