The Planner and the Gatekeeper

The difference between decision-making and action-taking

Published: 2024-12-01 | Last updated: 2026-01-09 by Luca Dellanna

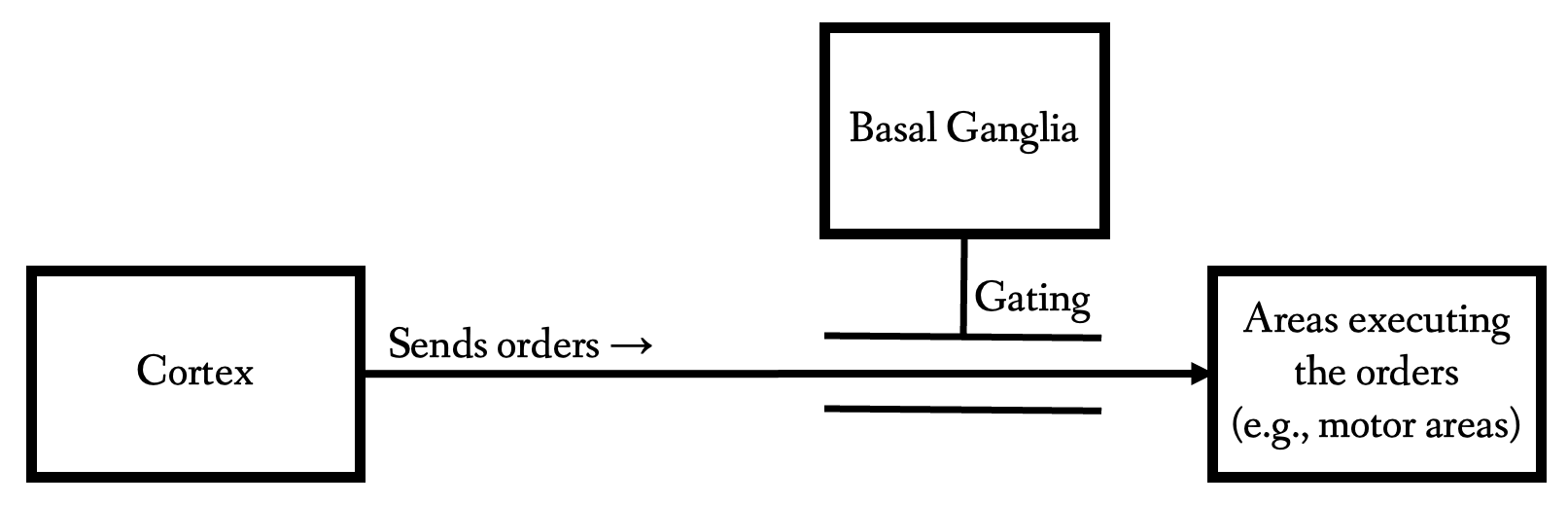

The interaction between the two, depicted below, determines most of human behavior.

A common example

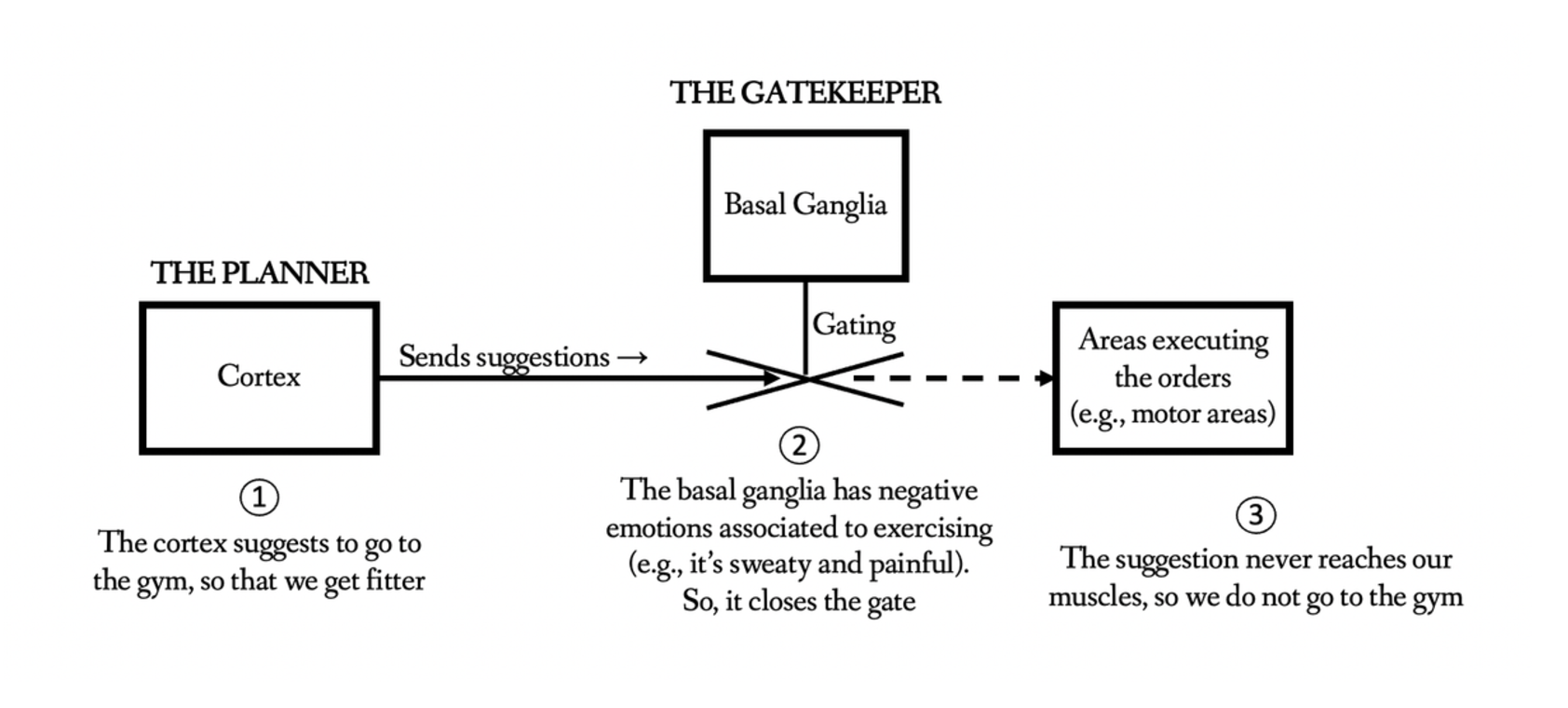

Imagine our cortex (the Planner) decides we should hit the gym. If our basal ganglia (the Gatekeeper) doesn’t like exercising, the cortex’s order doesn’t reach our motor areas, and we do not go to the gym.

What’s the result of liking an outcome but not the action that achieves it? Inaction, and thus, frustration.

The circuitry

The image below depicts a simplified schema of the actual circuitry that you would observe if you dissected a human brain. There is a pathway running from the cortex to the motor areas of our brain. Alongside it, there is an area of our brain called the basal ganglia that can inhibit the pathway, preventing the cortex’s orders from becoming actions.

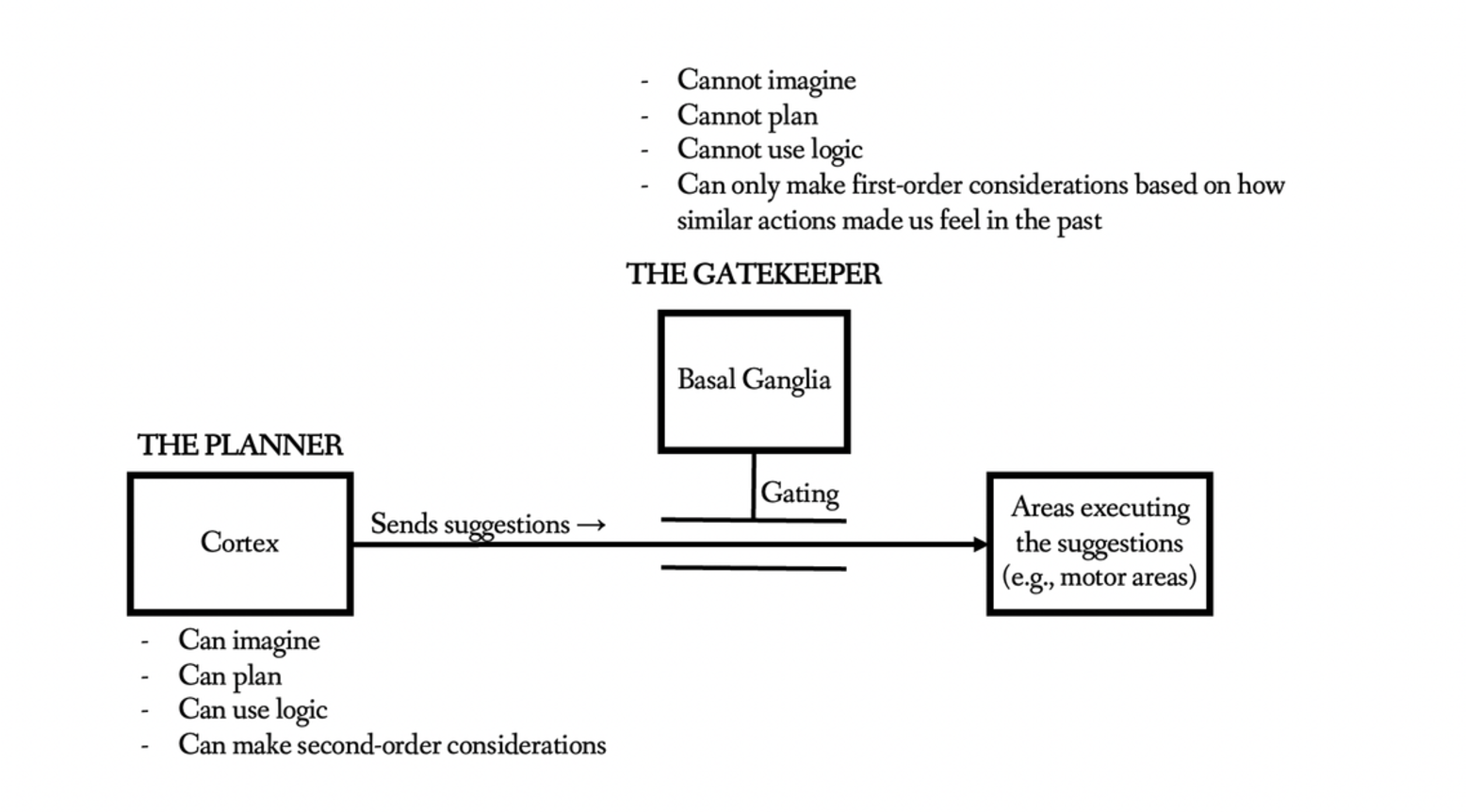

This circuitry highlights a separation of roles.

The Planner (our cortex) makes plans but does not have direct access to our muscles; therefore, its plans are only suggestions.

Conversely, the Gatekeeper (our basal ganglia) cannot make plans but can block the Planner’s suggestions from reaching our motor areas.

For action to occur, our cortex must suggest it, and our basal ganglia must approve it. If either is missing, we do not take that action.

Habit formation

To create new habits, we must ensure that our cortex sends the desired orders and that our basal ganglia allow them to reach our motor areas.

Sadly, most habit formation advice addresses only the former. It involves either making better plans or removing cues from our environment so that we do not come up with bad ideas (such as eating that bag of chips on the table).

However, that is cortex-centric advice that ignores the Gatekeeper. No wonder it is not very effective.

Influencing the Gatekeeper

So, what causes the Gatekeeper to open or close the gate? It’s simple: experiential memory. The gate opens when the suggested action is remembered to have brought positive emotions in the past.We have already seen that the Gatekeeper cannot imagine or plan, only remember. The part of you that can imagine, plan, and consider indirect or long-term consequences is the Planner, not the Gatekeeper. Knowledge, imagination, and planning help generate good suggestions but do not guarantee execution, nor do they prevent bad ideas created by instincts.